Only half of Greenlanders know that climate change is caused by humans

By Ole Ellekrog

A couple of years ago, the American PhD student Kelton Minor and his team of Greenlandic research assistants were staying at Arctic Station on the outskirts of Qeqertarsuaq, Disko Island. They had come to conduct interviews with locals on their perception of climate change in Greenland.

On their first day, as the group left the research station to head to town, the director of the station noticed something was off. His guests were not behaving as they usually do. “Huh, this is interesting,” he said: “Usually, all the researchers head that way,” he said, pointing to a path leading the other way, to the vast backcountry of Disko Island.

“This was a personally meaningful moment for me,” Kelton Minor recalls: “It showed me that what I had noticed in the scientific literature was correct.”

What Kelton had noticed was that a lot of international scientists come to Greenland to study climate change and its effects on the natural environment. But very few researchers talk to the locals about their experiences of the changing climate. In fact, and Kelton had noticed this too, Greenland was one of the only countries in the world that had not been included in national surveys on the perception of climate change between 2010-2021 (after the ‘The Self-Government Act’ was passed in Greenland).

Some details from Kelton Minor’s PhD: The map (a) shows how many times a country has had national surveys on climate change conducted. (b), (c), and (d) show the perception of climate change in selected countries.

Source: Kelton Minor

Counter-intuitive results

Kelton Minor, who was studying at the University of Copenhagen at the time under the supervision of Minik Rosing, decided to make this national survey the subject of his Ph.d. So, through posts on social media and posters on the walls of Ilisimatusarfik, the University of Greenland, he and Swedish PhD student Gustav Agneman recruited a group of local research assistants.

Together, they travelled around towns and villages in each of Greenland’s regions, including Qeqertarsuaq on Disko Island, where they conducted in-person interviews with residents who had been randomly selected by Statistics Greenland. Later, the in-person interviews were supplemented by phone interviews that reached 1585 people in total, 4 percent of the entire adult population of the country.

The map on the left shows the locations of residence of all the people that were interviewed for Kelton Minor’s project. The yellow square shows in-person interviews and the purple circles show the location of people interviewed by phone.

In the figures on the right, the results are shown across the different municipalities of Greenland. You may notice, for instance, that the people from North West Greenland (Avannaata and Qeqertalik) and East Greenland (East Sermersooq) are both the people who experienced climate change the most and the people who are least aware that it is caused by humans.

Source: Kelton Minor

As a result, Kelton knew that his data was highly representative of Greenland’s population. Now, all that was left to do was to analyze it and see, for the first time, what the population of Greenland really thought of climate change. This analysis led to several surprising and important findings – so important that they were recently published in Nature Climate Change, the world’s most prestigious scientific journal on climate change.

“Some of the results of the survey are really interesting and quite counter-intuitive,” Kelton Minor said.

Knowledge should be shared in Greenland

And then what were the surprising results?

Kelton Minor singles out three core findings:

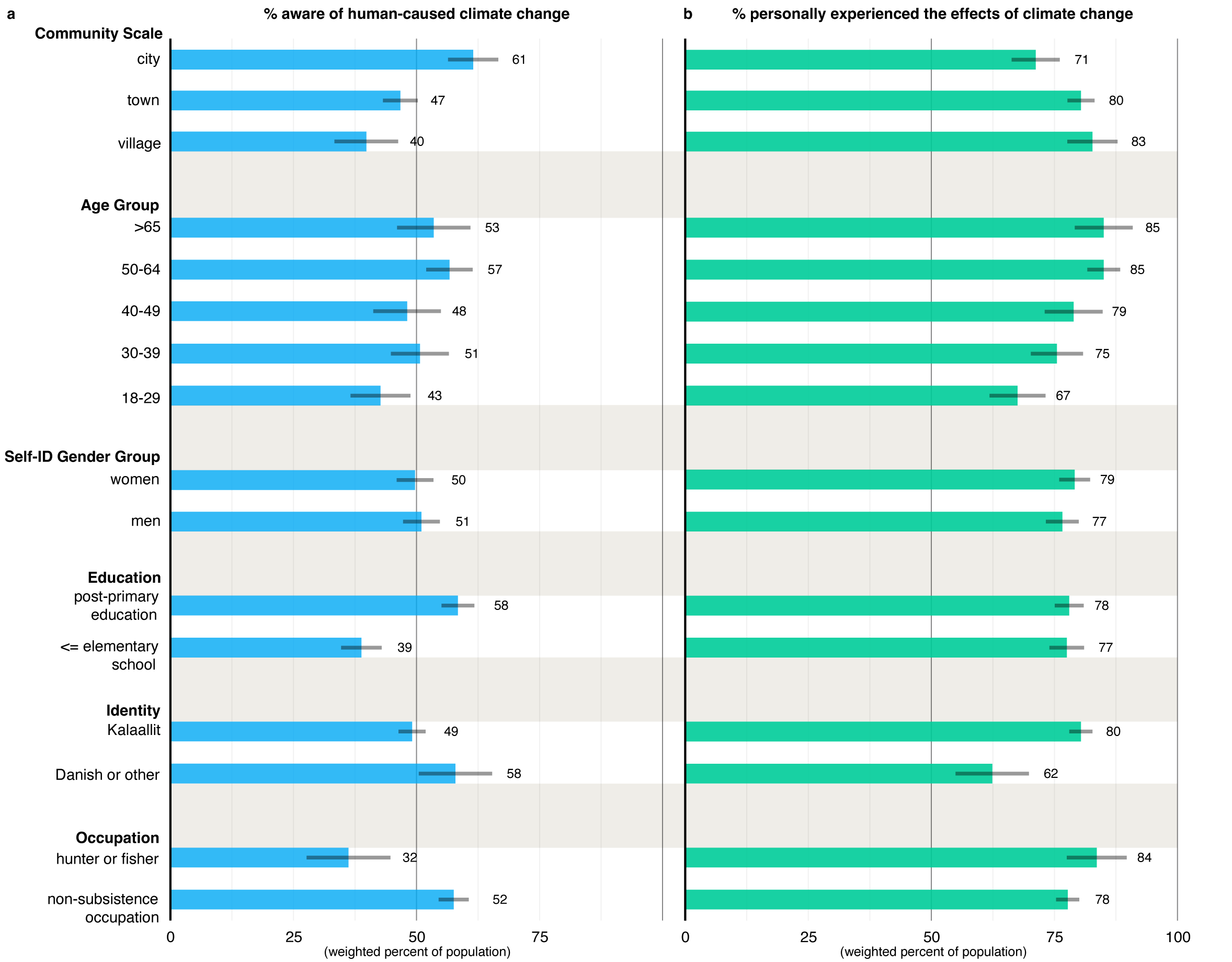

- 8 out of 10 people in Greenland have personally experienced the effects of climate change – twice as many as in any other Arctic country studied.

- Only half the population of Greenland are aware that climate change is caused by humans.

- Within Greenland’s population, the people who experience the impacts of climate change the most, are the least aware that climate change is caused by humans.

These three findings show Kelton Minor that things could be improved. That more could be done to help share the knowledge gathered by all the climate researchers coming to Greenland.

“99 percent of climate scientists agree that climate change is caused by humans. So, it is striking that one of the core insights from climate science, derived in part from Greenland’s ice sheet and surroundings, is not being shared widely enough with the Greenlandic public,” he said.

More knowledge, more opportunities

More awareness would not only help the people of Greenland better understand the changes around them. According to Kelton Minor, it could also lead to new opportunities.

“Being aware of human-caused climate change may change the way that people view their own opportunities in Greenland. It is linked to the support of policies that are adaptive to climate change,” said Kelton Minor.

As an example, he mentions a recent proposal to extract and export sand transported by Greenland’s melting ice sheet. This was supported more by people who were aware that climate change is caused by humans than by those who were not.

“The perceptions of the causes and consequences of climate change are of great importance for society’s climate adaptation.”

– Minik Rosing.

And Kelton’s PhD-supervisor, the world-renowned Greenlandic geologist Minik Rosing, who’s the man behind the sand project, agrees.

“The perceptions of the causes and consequences of climate change are of great importance for society’s climate adaptation. Therefore, it is also important to know how these perceptions are shaped,” says Minik Rosing.

The youth are least aware

Another surprising finding in Kelton Minor’s project was that young people are less aware than older people that climate change is caused by humans. This pattern, which is opposite to what you find in most other countries, indicates to Kelton Minor that education on climate change in Greenland could be expanded and introduced earlier.

On these graphs, you can see how the knowledge and experience of climate change is spread across the population of Greenland. For instance, you will notice that people in villages have experienced climate change the most but are also the least aware of the human origins.

Source: Kelton Minor

“We need to improve access to climate science via the engagement of Greenland’s civic institutions, Kalaallit-led teacher training, and curriculum development that integrates the insights of climate scientists and local knowledge of climate change from around Greenland. Educational opportunities should also be promoted in society because having access to secondary education helps increase awareness of human-caused climate change,” said Kelton Minor.

In addition to this, he also believes that more could be done by news media and weather forecasters. He recommends that those working in these fields should be aware of the connections between human-caused climate change and the weather conditions in Greenland, including the changing sea ice. This would help the larger public put the changes they observe into a larger context.

Things to learn from Greenland

Kelton Minor and his co-author Manumina Lund Jensen have another important point to make. Because the people of Greenland are not the only ones who could benefit from more contact with the climate scientists visiting their country. A lot of learning could also move in the opposite direction.

“Being aware of human-caused climate change may change the way that people view their own opportunities in Greenland. It is linked to the support of policies that are adaptive to climate change.”

– Kelton Minor.

In particular, in the study Manumina Lund Jensen who is a Cultural Historian at Ilisimatusarfik, the University of Greenland, emphasizes the Inuit concept of ‘Sila’, which is the Greenlandic word for both “the weather” and “the mind”. It has a deep spiritual significance in Greenland and its double meaning demonstrates how closely the climate is linked to the lives, psyches and identities of Greenlanders.

“I think it is equally important that Indigenous knowledge about sila is communicated. This shouldn’t be separate from climate science but presented at the same time to show meaningful ways of thinking about the climate and the world. Bringing diverse forms of knowledge and experience together is central to the idea of ‘convergence research’ which can support adaptation to the changing conditions in Greenland,” Kelton Minor said.

Climate scientists are resonating

In the future, Kelton Minor hopes that this mutual knowledge exchange between climate scientists and the people of Greenland will grow stronger and start more conversations. He hopes that more researchers visiting Greenland will not just “head out for fieldwork” but will also “head into town” as Kelton’s team did in Qeqertarsuaq. This will help engage local communities in the scientific process and help the scientists respectfully share their research more widely with the public.

Happily, it would seem that his message is being heard. Less than 24 hours after posting their results on Twitter, more than 30.000 people had read his tweet and their online article in Nature Climate Change has been accessed over 6,000 times in just the first few months since it was published.

“There has been a huge reaction online from climate scientists that work in Greenland. People are resonating with the realization that climate science needs to be better shared with the populations that are most impacted by climate change,” Kelton Minor said.

Kelton Minor, who is now working as a post-doc at Columbia University in the USA, hopes to continue his work on climate change perception in Greenland. Next, he and Manumina hope to combine in depth interviews with national surveys to better understand what people are experiencing.

“I consider the people living in Greenland as scientists themselves, even though they may not think of themselves that way. Everyone is an expert on their own lives and their own knowledge,” he said.