Najaaraq examines Greenland’s trust in the public institutions

By Ole Ellekrog

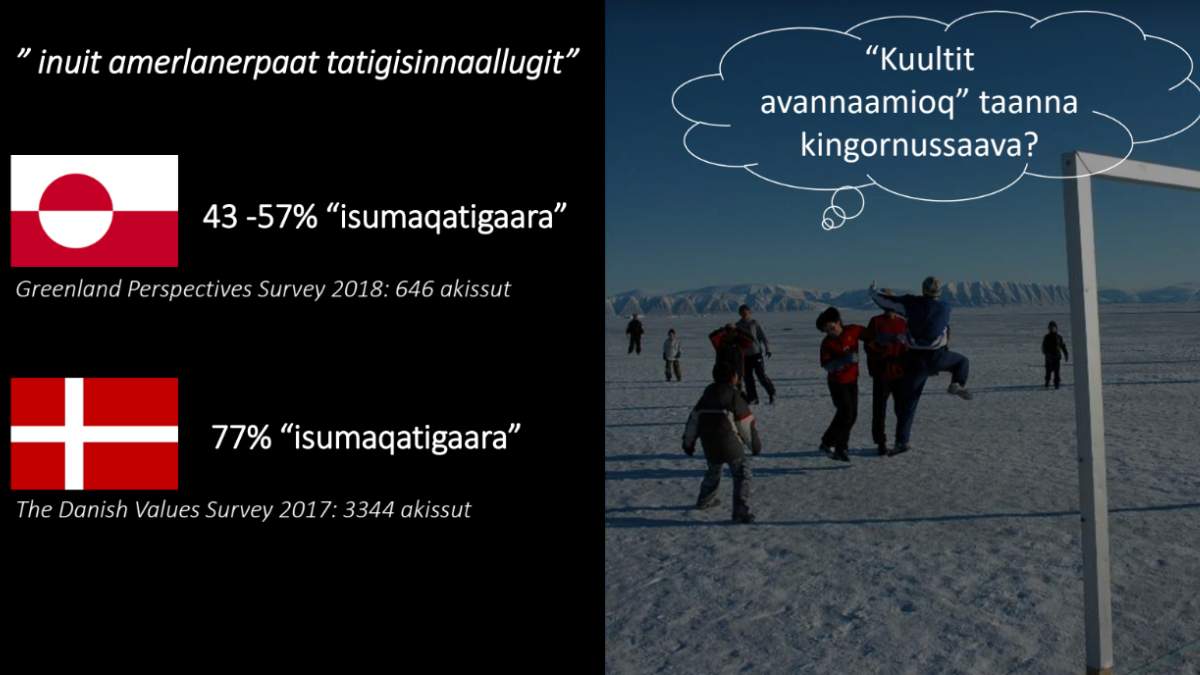

“Most people can be trusted.”

If you said that phrase to a kaffemik in a random place in Greenland, you would probably be able to divide the participants into two roughly equal groups. Those who agree and those who do not. In a survey from 2018, 43 to 57 percent of Greenlanders responded that they agreed with the statement.

Attitudes towards this statement vary enormously depending on which country you examine. Some strongly disagree. In Zimbabwe only 2.1 percent agree, in Peru the figure is 4.2 and even in a European country like Greece the figure is only 8.4. Globally, Greenland’s level of trust is actually relatively high.

The interesting thing is that Denmark, from which Greenland has inherited its political system, is right at the top of the lists. In a survey from 2017, 77 percent of Danes thus agreed with the statement.

“I discovered quite early on that the question of trust was absolutely central”

– Najaaraq Demant-Poort

There is a significant difference between Greenland and Denmark, and Najaaraq Demant-Poort, assistant professor at Ilisimatusarfik, University of Greenland, would like to understand whether these differences mean that the way we run the public Greenlandic institutions (government, parliament, municipalities, police, trade unions, defense, etc.) might not fit Greenland’s trust values.

That dilemma is what Najaaraq is investigating in her PhD.

Must trust that the legislation will work

Before Najaaraq Demant-Poort became a researcher, she worked for 10 years in Greenland’s Government. It was here that she noticed how some elements of the administration’s practice did not always suit Greenlandic society.

The level of trust is lower in Greenland than in Denmark.

Graphics: Najaaraq Demant-Poort

“I discovered quite early on that the question of trust was absolutely central. When we had to implement some legislation we had inherited from Denmark, it often required citizens to trust that the regulation was the right one and would work,” says Najaaraq Demant-Poort.

“The legislation in the area I worked with, for example, involved a lot of scientific expertise. When something like this has to be implemented with our current system, trust is required in many of the relationships. For example, between citizens and politicians, politicians and civil servants, civil servants and experts,” she says.

Created it herself

During her time in the Government, Najaaraq became more and more convinced that such dilemmas of trust are absolutely crucial for some of the challenges faced by Greenland’s institutions.

Before she became a civil servant, she had taken a Master’s degree in Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. Therefore, she also had knowledge of the research on the topic and could see that the issue of trust was under-examined in Greenland.

“Much points to the fact that there could be a need to change some of our institutions so they are better suited to Greenlandic conditions”

– Najaaraq Demant-Poort

“It was a long process to figure out if I was on the right track and if I could turn my hunch into a good project. But I received a lot of support from everyone I talked to and therefore decided to go ahead with it” says Najaaraq Demant-Poort.

When she had become convinced that her idea was worth investigating, she applied for and received a grant for a pilot project from the Greenland Research Council. Since then, she was employed as an assistant professor at Ilisimatusarfik, where she works and does research today.

Why is it important for Greenland?

And what was it that made everyone tell Najaaraq that her wonder was worth investigating? Why should Greenland consider whether the population has different values for trust in each other – and in the institutions – than in Denmark?

Greenland should do so because it can be the root of some of the things that do not work in the public sector, Najaaraq explains.

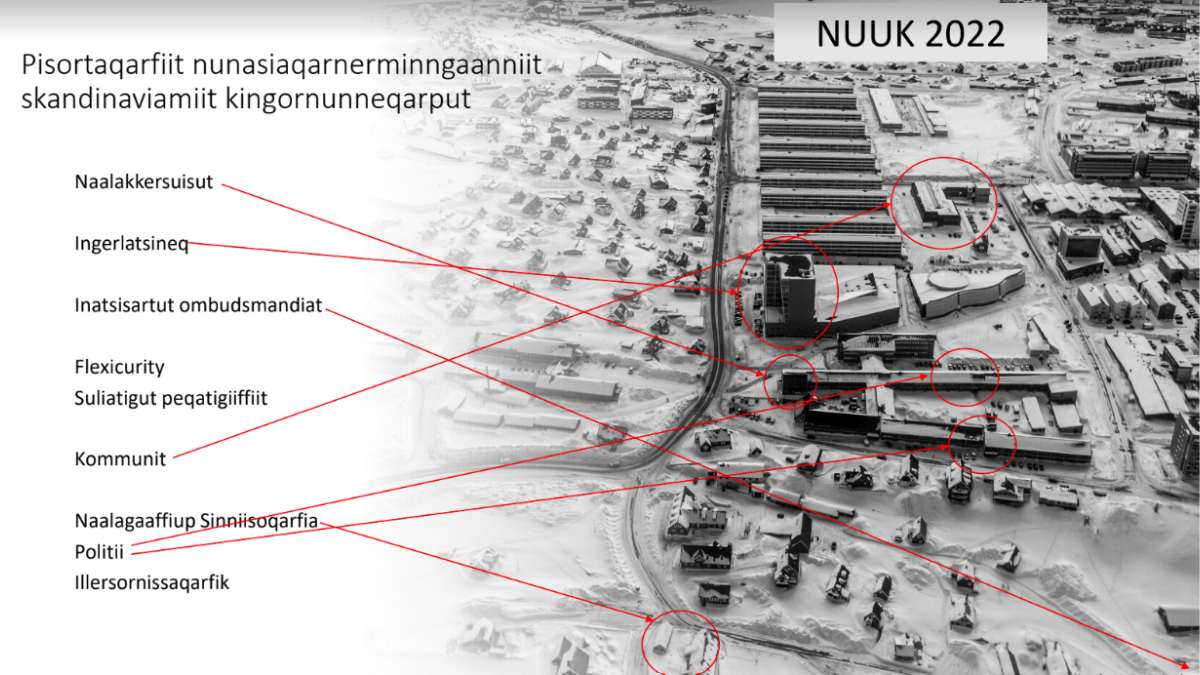

“The Scandinavian model is a role model in other parts of the world, and is famous for many things: for example, high welfare, high quality of life, and a stable economy. Many connect those things to the high level of trust. But here in Greenland, we just have a completely different situation,” she says, and continues:

“Here we have inherited the institutions through a process of colonization, but we run them as if they should function in the same way as in other Scandinavian countries.”

Here it is illustrated how central institutions in Greenlandic society are inherited from a Scandinavian model.

Graphics: Najaaraq Demant-Poort

She points to three concrete examples where there are signs of inconsistency between Greenland’s trust values and the trust ideals that the system requires:

– 1. Lack of reforms

Firstly, she points out that the public sector continues to grow, even if nobody wants it to. The trust that has been described as an “oil in the machinery” that makes the public sector in the Nordic countries efficient, apparently does not work in the same way in Greenland.

“Our politicians have repeatedly said that we need a reform of the public sector and that we must have less bureaucracy. But the opposite is happening.

– 2. Non-payment of debts

Another point Najaaraq mentions is that many do not pay the money they owe on time.

“We have a huge tax arrears (failure to pay on time). Many do not pay their taxes or other debts as they should,” she said.

– 3. Multiple control mechanisms

And the third point she points to is that there is a need for control bodies in many areas, as everyone does not comply with the rules.

“For example, the rules on reporting fishery catches are not always followed, and you therefore have to set up expensive controls to make sure that people comply with the rules,” she said.

“These things, among other things, could be rooted in the fact that some of the ideals in the Scandinavian system do not suit Greenland,” says Najaaraq Demant-Poort.

Greenland must find its own way

But Najaaraq does not only spend time identifying the problem, she also tries to find solutions to it. However, she will not come up with proposals for extensive changes in the Greenlandic system herself.

Trust is a central theme in Najaaraq’s research.

Photo: Lars Demant-Poort

“Much points to the fact that there could be a need to change some of our institutions so they are better suited to Greenlandic conditions. But I don’t know exactly how it should be done yet. It requires us as a society to start a dialogue about what we really want from the public institutions,” she says.

To find solutions, she also looks at research from other countries. Among other things, research in Sweden, Finland and Norway, where similar studies have investigated trust among the original Sami population. But countries far from Greenland and the Arctic are also relevant.

“It’s all about being safe and trusting the system, and that’s what my research focuses on”

– Najaaraq Demant-Poort

“The interesting thing is that when you look at other colonized countries around the globe, you can see a lot of common features with Greenland. The difference in trust values may also arise from the unequal power structure that is a result of the countries inheriting their institutions from elsewhere,” she said.

Won competition in Iceland

Najaaraq’s results are therefore part of a wide-ranging international discussion, and are important to spread, also outside Greenland. And she did just that when she presented her research to a competition during the Arctic conference Arctic Circle Assembly in Iceland.

Here, her project won ahead of 12 other Arctic research projects.

She herself thinks it was because she made the research relatable. She described a situation that everyone can relate to.

“I talked about the feeling that comes over you when you get a letter from the municipality and suddenly get really nervous. That picture illustrates very well that we all have certain expectations when we have to interact with a public institution,” she says, and continues:

“That feeling is formed by many things: by our previous experiences with the institution, by our upbringing or by our knowledge of the system. It’s all about being safe and trusting the system, and that’s what my research focuses on,” she says.