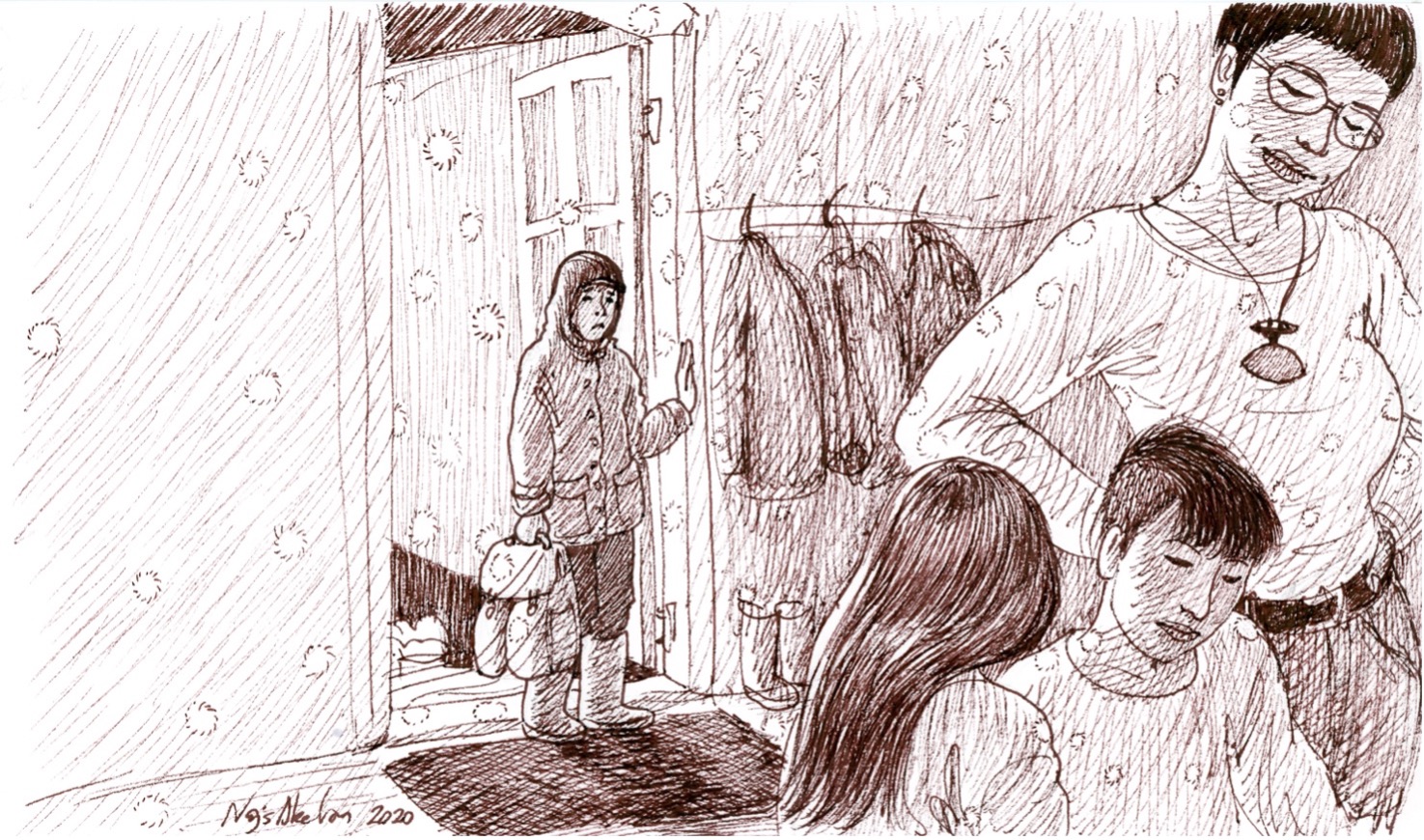

Some of the many Greenlandic children living in out-of-home care across the country are not thriving, according to a new Phd dissertation.

By Laura Philbert, Polarfronten

Every year, more than four times as many children in Greenland are placed in out-of-home care and in residential institutions than Denmark. But according to Bonnie Jensen, assistant professor at Illisimatusarfik – the University of Greenland, we lack real knowledge about what the children actually think about living in these institutions. In connection with her PhD dissertation, she has spoken to 38 children across the country. The conversations show that some children live in what she calls a constant state of insecurity. Bonnie Jensen, who has worked with vulnerable children and young people throughout her entire working life and has been responsible for all children’s out-of-home care in Greenland, says:

“One of the things that has made the biggest impression is how little the children know about their own lives. Many of them don’t know why they are placed or how long they can be allowed to stay where they are. Some of them are afraid that someone may come in half an hour, tomorrow or next week and say that they have to move to another place. Imagine having to live with that uncertainty.”

She explains that about half of the children she has spoken to are not happy living where they live.

“We place children to make them feel better than they did where they were before. That’s the starting point. And how can we make sure the place they live is better than the one they came from? Only by asking the children if they feel well where they live,” recommends Bonnie Jensen.

Her primary criticism is that the initiatives already in place to help the children are failing because they are based on how the adults think the children are doing. “We lack basic knowledge about the area, and we lack better insights into how children feel about being placed. The more you know, the easier it is to find solutions,” she says.

Want closer ties to adults

Based on her conversations with the 38 children, she points out that an important task lies ahead in relation to the pedagogical work. Many of the children say that they miss having closer ties to the adults in the out-of-home cares.

“The children want more ’good adults’. According to the children, good adults are those who have time to go for a walk, time to listen and just be there for them, and who doesn’t scold too much. Just like all other children,” says Bonnie Jensen.

But if the children are to feel safe enough to form good relationships with the adults, they need to overcome the insecurity that many of them live with.

“The pedagogical work at residential institutions is based on relationships, and it’s extremely difficult to establish a relationship with someone, if you don’t know if you, or they, are going to be there tomorrow.”

In Bonnie Jensen’s conversations, it turned out that the places where the children were happy to live came down to where they had good relationships with the adults. And where the children were not happy to live, it owed to a lack of family and lack of relationships with the adults.

“It goes hand in hand, because if you are in a place where you’re really happy for the adults, then the longing for your mother is perhaps easier to bear,” says Bonnie Jensen.