The ground-eye view gave scientists new insights into wildfires

By Kevin McGwin

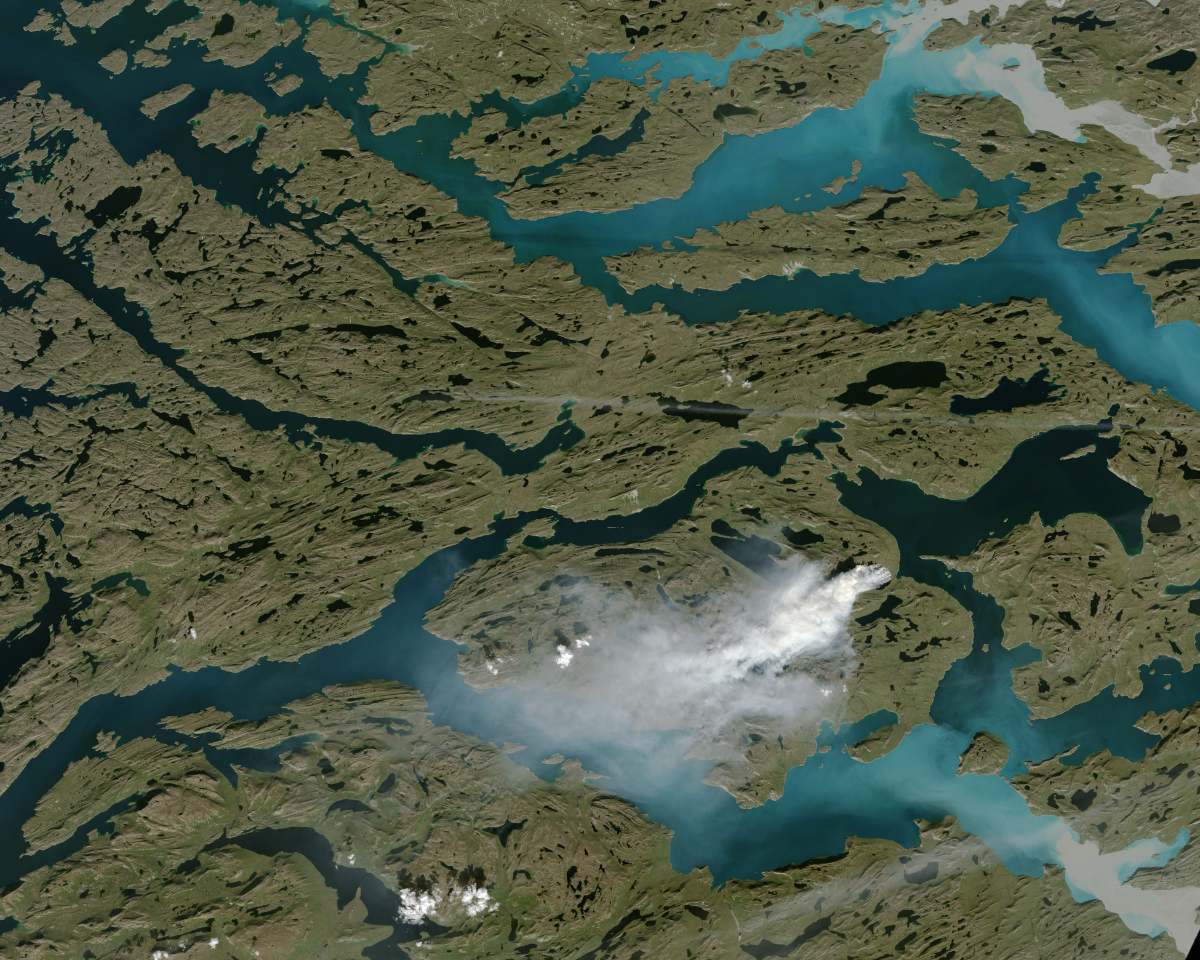

Where there is smoke, the saying goes, there is fire. And, if you are a scientist studying something like the increasing problem of wildfires in the Arctic, one good way of finding out where the fires are is by looking for tell-tale plumes of smoke in satellite images.

The media can also be a help. Looking through news articles helps scientists identify blazes that satellites might not have picked up, and, with input from fire services, these reports can provide an indication of how they might have started.

But, in a place as vast and as sparsely populated as Greenland, it is easy for fires to escape the eyes of earth-monitoring satellites and the media. So, when research conducted after two unusually large wildfires in 2017 and 2019 made it clear that the phenomenon is becoming more frequent, Harold Lovell and Mark Hardiman, both of the University of Portsmouth in the UK, questioned whether there was more to the picture than the satellites were telling them.

Interviews reveal additional fires

To find out, the two teamed up with Pelle Tejsner, an anthropologist with Ilisimatusarfik / University of Greenland, to speak with the people who were likely to have first-hand knowledge of unrecorded fires.

“There is a lot more information about these fires than we can glean from remote sensing or an archival approach,” Lovell says. “By talking to people in Greenland, we learned not just whether there were fires, but also how they were perceived and how they affected everyday life.”

“By talking to people in Greenland, we learned not just whether there were fires, but also how they were perceived and how they affected everyday life”

– Harold Lovell

The result of the workshops and interviews they conducted last year in Nuuk and Sisimiut was that there were indeed more accounts of fires than they had documented.

Firefighters work to contain the Kangerluarsuk Tulleq fire. Their efforts were hindered by challenging terrain and dry conditions that allowed the fire to spread underground. Photo: Nanna Stahre

Kangerluarsuk Tulleq fire

In July and August 2019, Greenland’s largest recorded wildfire took place in the Kangerluarsuk Tulleq area, some 20km north-east of Sisimiut (pop 5,500). The fire was caused by a traditional fish-smoking oven. Initially, the Sisimiut fire service thought it had extinguished the fire, but it continued to smoulder beneath the surface, burning through peat that had been left parched by a period of extreme drought. After a month of working unsuccessfully to put the fire out, Greenland asked for assistance from the Danish emergency management agency, which used harpoons to pump water into the ground.

There were reports of a fire occurring sometime in the 1980s, but, according to Lovell, there is a “culture of consciousness” of the danger of fire amongst people who use the land, both underscore that fires are not a new phenomenon in Greenland. What has changed, the discussions revealed, is how unpredictable and how extreme the weather has become.

“When we talked to people, everyone mentioned how unusually dry the weather was when the big fires occurred,” Lovell says. “On the other hand, the summers have been extremely wet the past few years, but everyone told us it wouldn’t take much before we saw the same conditions that led to the 2017 and 2019 fires.”

The good news is that, while those two fires got a lot of attention, they were small in comparison to fires in other parts of the Arctic. And while fires remain rare, they are becoming increasingly common: whereas Lovell and Hardiman found no reports of wildfires between 1995 and 2007, there have been 21 fires in the years since. Speaking to people to identify previously unrecorded fires (a process known as participatory mapping) suggests there have been even more.

“No-one was telling us fires are happening all the time,” Lovell says, “but what they told us revealed that there was a richer history of fires in the region than we expected.”

Mark Haridman (left) and Pelle Tejsner prepare for one the two community meetings held in Nuuk and Sisiumiut last year. During the meetings, participants were asked to identify where they had observed wildfires, and to describe how they have come to affect their daily life. Photo: Harold Lovell

During the workshops in Nuuk and Sisimiut, residents were asked to identify where fires had taken place. The vast majority were in areas that were used for hunting or recreation. Photo: Harold Lovell

Because fires in Greenland tend to be small, and their impact limited, knowledge of them typically doesn’t spread beyond the immediate area. But speaking with representatives of fire services, the national museum and the tourism industry revealed considerable concern.

“There is an awareness among authorities and elders that this is a risk, be it to tourism or to cultural heritage or to hunting activities, even if there is no guarantee that fires will be something we see on a regular basis,” Lovell says.

Still, the conditions are increasingly ripe for fires: there is more potential fuel in the form of increased vegetation, and more frequent periods of dry weather are leaving the ground parched, setting up ideal conditions for peat fires that can burn underground for weeks without being noticed. This was the case with the 2019 fire, which eventually had to be put out by a team of 38 emergency responders from Denmark. Even using specialised equipment, it took them the better part of two weeks.

More aware, better prepared

Those experiences have led to what Lovell describes as “collective heightened awareness” of the risk of fire among people who use the land, as well as to a better-prepared, better equipped fire service.

“People weren’t oblivious to fire before, but the 2019 fire burned for two months and affected people in a way they hadn’t been impacted by fire before,” he says. “That’s left its mark.”

While Greenlandic authorities are already doing significant work to prevent and to prepare for wildfires, according to Lovell, understanding the perspective from the ground could allow them to spend more on the former and less on the latter.

“It’s not certain that we’ll see another large fire of the sort we can see from satellites, but it is likely we will see the conditions that can lead to one,” he says. “And it’s important for people who use the land to be aware when there is a risk of fire and what they can do to minimise it.”

Wildfires in Greenland

There is no satellite evidence of fires in Greenland until 2008, and only sporadic accounts in the media. After 2008, they have been recorded in most years, and, since 2015, the intensity and number of fires recorded by fire services has increased significantly.

Most fires are small—typically located near camping huts—and only identified after they have burned out. But projected warming and unpredictable summer vegetation suggest groundfires could become more common, more intense and harder to put out.

Fires are often located in difficult terrain far from water sources. When conditions are dry—and fires most likely—supplying enough water to fight them will be challenging.

Smoke from major fires can disorient hunters and hikers. During the 2019 fires, one group of hikers on the Arctic Circle Trail between Sisimiut and Kangerlussuaq had to be evacuated, while the local authority issued a general warning to stay clear of the area.

Hunters report caribou herds being “spooked” by the 2019 fires, and there have been reports of smoke blackening the lungs of caribou.

Topfoto: Flames consume vegetation during the Kangerluarsuk Tulleq fire. While Greenland’s surface plants are normally not considered a fire risk, they can add to intensity of underground fires, particularly during drier conditions. Photo: Nanna Stahre