Researchers collaborate with Greenlandic fishermen, catchers, and schoolchildren to map how much the country rises.

By Uffe Wilken, Polarfronten

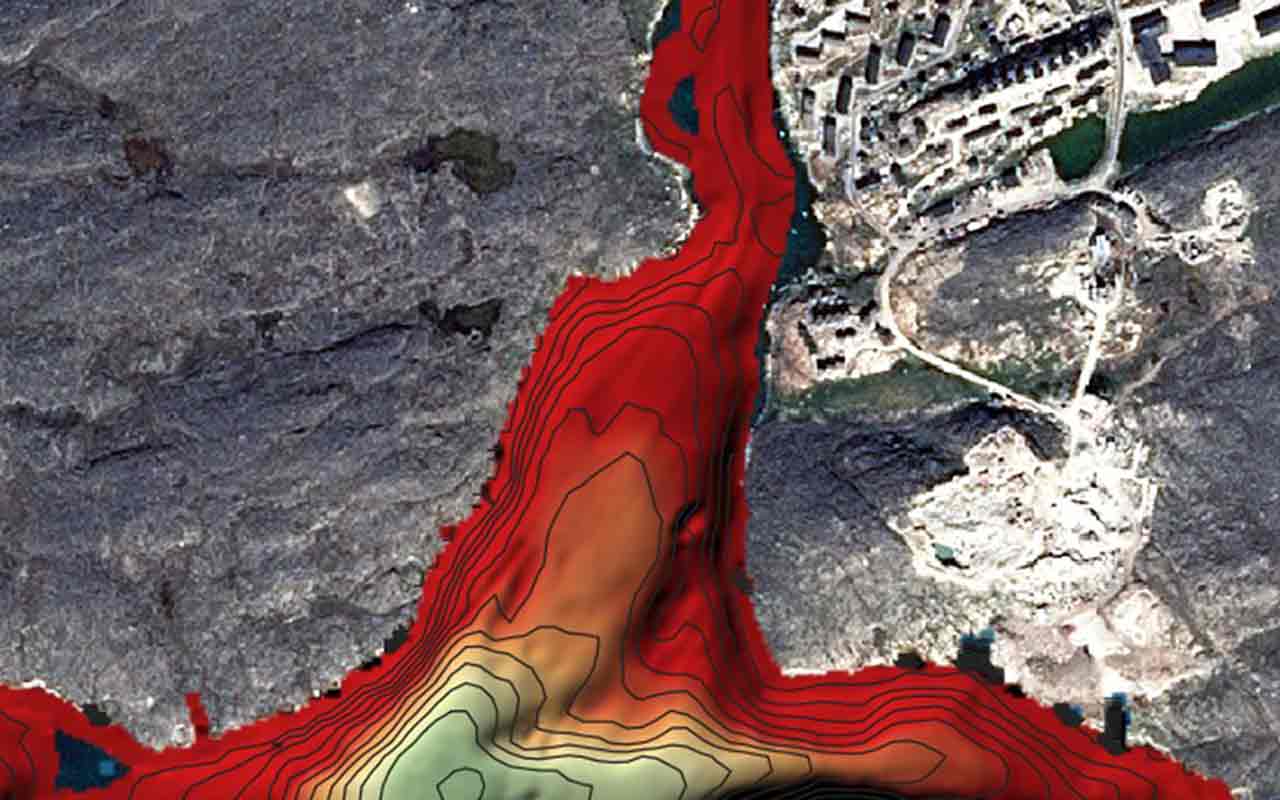

The statement Greenland rising must be taken literally because Greenland is rising, and the Greenland Rising project aims to measure and predict how much it will rise in the coming years. Although it is only about a few millimeters each year, it may have a significant impact on the sailing in the fjords and for construction projects like ports, quays, and drainage in the long run. In some places, the rising over the last few generations have already had consequences. Project coordinator Karl Zinglersen from Pinngortitaleriffik (Greenland Institute of Natural Resources) says:

“When we’re out on field work, we get to talk with the locals. Some of the elders have experienced that they can no longer access certain areas where they used to be able to sail. But now some of the slopes are a bit higher, so the locals need to take another route than the one they used to take. We’ve heard several examples of this, and it’s interesting that the local population can see what we’re measuring here. It’s nice to know for us, because even though we’re talking millimeters, it matters over time.”

The ice is crucial

Two things decide how much Greenland will rise. One is the melting of the ice sheet since the end of the last ice age roughly 10,000 years ago. Less ice means that the weight of the ice is no longer pushing down the land, and, thus, the land is going to rise. But since the ice is disappearing at different speeds in different parts of the country, the rise is not consistent.